The Representation of Gender in PBTA Games as Aesthetic or Ontology

In Romance languages, and Indo-European languages in general, nouns tend to be classified by 'gender'. For example, in Latin the word 'aqua' (water) is feminine, the word 'amicus' (friend) is masculine, and the word 'simulacrum' (likeness) is neuter. In the study of grammar, the term 'class' may be used instead of 'gender' when referring to classification systems of nouns that do not correspond to gender. For example, Basque classifies nouns according to whether they are animate or inanimate; Swahili has 9 noun classes for people, plants, liquids, tools, animals, and more. Indo-European constructs of language are not universal, and labeling the grammatical role of 'gender' as 'class' is more accurate, and it encompasses more languages than just those who classify nouns based on gender alone.

In indie tabletop role-playing games, we've seen almost the opposite move. Class-based gameplay (e.g. cleric, fighter, mage, thief) has been surmounted either by classless gameplay, or by PBTA games which replace classes with 'playbooks': extra-specialized classes which represent a generic archetype for the setting of the game, and which only one player in a game may select to play. Unlike how D&D classes each describe a sort of basic role a party member might play, PBTA playbooks each tend to describe a special role/persona. For instance, in a five-member band there's only one Frontman, one Lancer, one Smart Guy, one Big Guy, and one Chick. That sort of deal.

Playbooks also offer aesthetic choices ('Looks') to the player alongside mechanical ones, to reinforce the literary symbolism of the specific playbook. In D. Vincent and Meguey Baker's Apocalypse World, the Battle Babe might have a 'sweet body, slim body, gorgeous body, muscular body, or angular body', while the Chopper might have a 'squat body, rangy body, wiry body, sturdy body, or fat body'. Despite each individual choice working to make one instance of the Battle Babe distinct from another (thus making a player character feel more unique to that player), all together they represent the complete set of individuals which can be represented in the form of the Battle Babe. In the genre which Apocalypse World attempts to emulate, it doesn't make sense for a Battle Babe to look fat any more than it would for a Chopper to look girlish.

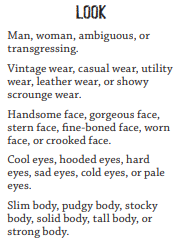

Although there's certainly something to unpack there (I'd venture to say there's nothing wrong with codifying aesthetic for character archetypes in itself when the same thing occurs in media in general, and we ought to look at what exactly is being codified instead), I wanted to write about one of the 'Looks' categories found in both Apocalypse World and Monster of the Week. I will attach one screenshot from each of these games.

Neither game explicitly labels each category of looks (e.g. 'Clothing, Body, Eyes, Face'). This means that when reading the top category of each list, we are left to interpret exactly what it entails to ourselves. It definitely represents a selection of gendered presentations. Does it represent the character's gender as such, i.e. is it an ontology of the character? Is it just an aesthetic choice without any bearing on how the character behaves? Is there a difference between being and aesthetic when each player character represents a generic archetype par excellence? I think that Baker is wise to leave this unsaid, and (it seems) to focus on their aesthetic value without spelling out what it means for the character's being.

Not only is each category here labeled, but 'Look' is now a category of 'Identity' alongside 'Name', 'Eyes', and 'Origin'. It would not be fair to the author to describe this as a total inversion of previous PBTA games: indeed in Apocalypse World there are selection lists for your character's name based on their archetype, and having a selection of origin stories is not a far cry from anything.

However, Alder's choice to put all these character aspects under the category of 'Identity' speaks to Monsterhearts' ontology of the individual person. In parlance, 'Identity' tends to refer to the essential nature of a person (whereas I think that's a bad choice of a word for a bad premise). The verb phrase "I identify" takes on an existential nature as a declaration of being; it's the same as saying "I am", except with a certain level of distance from the identification-of-being itself. Perhaps that distance signifies that what someone identifies with is a personal choice; perhaps it signifies an acknowledgement of disagreement from others, who may not identify that person the same way. I hope you get the gist.

By elevating 'Look' to a category of 'Identity', Monsterhearts identifies this category as an ontological aspect of the game subject themselves: i.e., you are how you look (or perhaps, you identify with how you look). Despite these aspects being codified to the essence of the player character, you might have noticed how Monsterhearts does not include a selection of gender presentations like other PBTA games. Perhaps this is best left to the player's imagination, of course, as an aesthetic choice and not an essential one.

Ontology of Gender in Dream Askew

In Alder's Dream Askew, we find yet another different codification of aesthetic and ontology. I have screenshotted part of the playbook for the Iris.

In this game, 'Name', 'Look', and 'Gender' are all disparate categories not unified under a single header except, perhaps, that of the playbook itself. Even without the use of the header 'Identity', this seems to identify each category as an essential aspect of the character represented by the playbook.The items which Dream Askew collects under the category of 'Gender' may raise some eyebrows for those who not readily accept it. As pictured, the Iris might be androgyne, emerging, ice femme, void, or gargoyle. The Stitcher might be bigender, agender, cyber dyke, transgressing, or raven. The Hawker might be high femme, genderfluid, dagger daddy, stud, or raven.

There is an undeniable genealogy from Apocalypse World's nameless category of gender presentations, to Dream Askew's selection of genders: the 'transgressing' type is found in both! However, there is a major difference in that Apocalypse World seems to disavow an essential nature to its selections by putting them under the header of 'Looks' (hence I refer to its selections as gender presentations, rather than genders as such). Meanwhile, Dream Askew identifies these selections as genders.

If the goal of Dream Askew in this respect is to expand the set of elements which might be considered genders, or to détourne the category of gender as such, I don't think it succeeds. For one, many of the genders given are themselves gendered according to 'real life' modern western notions: e.g. ice femme, cyber dyke, dagger daddy. These are supplemented by other genders which are not gendered by normal standards at all—e.g. raven and gargoyle—perhaps to equalize all these types and declare them as equally valid classifications of gender.

Yet, to me, this makes Dream Askew's notion of gender itself suspect. Each of the types it represents as gender can be said to signify a set of aesthetics and behaviors. For example, I'm sure the gargoyle is a nasty little creature of a person. However, reducing gender to the conscious selection of aesthetic and behavior (or 'identification' with a certain aesthetic and behavior) trivializes its effects on subjectivity.

Among other things I'm sure, it disavows the role of the body in gender: that is to say that gender is the classification of bodies by primary and secondary sexual characteristics.* I concur with Butler that these characteristics are only sexed in retrospect of gender, and that gender is what subjects an individual to their then-after-sexed characteristics. Cis-gender-sex and trans-gender-sex individuals both feel the repercussions of this subjectification by gender, in what might be termed (regardless of gender-sex) a castration complex. The standards of the ideal body and presentation are expected to be met in order that the individual may be fully identified as the correct gender-sex, and not an imitation or lesser version. By reducing gender to a conscious selection of aesthetic and behavior, Dream Askew disavows the castration which underlies both the assignment and lived experience of gender, alongside its effects (conscious and unconscious) on the subject.

* The classification of third or more gender types tend to not move beyond the classification of bodies (when they do not represent intersex individuals), but they supplement it with subcategories. Very common is the third gender of the male individual who takes on certain signifiers of femininity. However, this individual is not categorized alongside female individuals. When such an individual is esteemed by the community in which they exist, it ought to be asked why this individual or set of individuals is esteemed and not the women who express these signifiers in mundane contexts. I wager that the third-gendered individual is celebrated as someone who trespasses boundaries and lowers themselves to femininity. Of course, such an individual also does not correspond to what we consider trans-sex, nor do they themselves tend to 'identify' as trans-sex.

Unfortunately I haven't had the mental energy to properly comment but I just wanted to let you know that these last several articles you've posted are really interesting and thank you for sharing them.

ReplyDeleteHi there! Thank you so much :) It makes me happy to hear people find this interesting!

Delete