Abstraction, the Basis of Capitalism (Part 2)

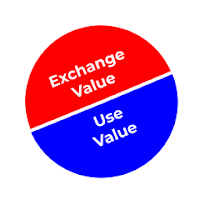

Marx in Capital, Volume I defines the commodity form as a dyad of use-value and exchange-value. This means that a commodity on one hand is a thing that can be used, that fills some need or want. On the other hand, a commodity is something which is exchanged on the market. Its value on the market is expressed as a ratio relative to some common denominator (i.e. money); this ratio is exchange-value. Marx argues thus that the capitalist economy is predicated on the abstraction of things into commodity-objects, with a social-value based on perceived usefulness expressed in terms of exchange-value [1].

This is an abstraction because commodities do not interact with each other in terms of their particular concrete use-values, but in terms of their social value expressed in exchange. A commodity stops being a commodity, something that can be exchanged, the moment it is used and consumed. You can trade money for a burger, but once you eat the burger, you can’t exchange it again; its use-value is consumed along with its social-value and, thus, its exchange-value. Exchange is the only situation where commodities matter as commodities; if they are not exchanged then they are just things, and their dimension as commodities does not matter and does not exist except virtually.

The determination of social value is also itself a system of abstraction. The classic liberal economists like Ricardo thought that the value of a commodity was a function of how much time it took to make that commodity. This is simply not true. Living in a capitalist economy, we have a social expectation of how long certain things should take to make. We know it takes many more hours to produce a smart phone than it does a mud pie, and only one of those things has any demand from society (thanks, Steve!). At the same time, I know I’m not the only one who feels like Apple is collectively ripping us all off because they have the brand power to get away with it—it’s not just a smart phone, it’s the iPhone XS or whatever the fuck! Commodities, Marx argues, are worth how much it costs for society at large to produce them, barring perhaps factors such as supply and demand that force firms to sell commodities below or above their value (Marx assumes a best-case capitalism as pictured by the liberal economists) [2]. The cost society expends is none other than the effort society expects to put into a thing—how much labor time society spends on average to produce a commodity.Capitalism must abstract particular kinds of labor into abstract labor so that the products of all these labors are comparable. That means it doesn’t matter whether you’re flipping burgers or painting fences; capitalism is blind to these particular activities. It sees only the production of commodities with social-values which are then expressed in exchange. By extension, just like the social cost of a commodity is the basis of its social-value (“How many of these does society make anyway?”), the basis of the abstraction of labor is the reduction of various concrete labors into how much effort society expects to expend doing them. In other words, the average time to produce a commodity—what Marx calls socially necessary labor time—is the only thing capitalism sees [3]. Capitalist society is the black box of capitalist production and exchange, and the objects thereof are only really abstract expressions of those relations. Ever wondered what Marx meant by commodity fetishism?

Postscript

I wrote the above months ago as part of me taking notes to try to relate all the big brain stuff I know, and how or why I think of them as being related together. Much more recently, I read an article by Ian Wright called "Marx on Capital as a Real God" on his blog Dark Marxism. For the most part, it explains why Marx characterizes capital as a real god or (as Wright calls it) an egregore, "a non-physical entity that exists in virtue of the collective ritual activities of a group yet operates autonomously, according to its own internal logic, to materially influence and control the group’s activities" [4]. This already has very interesting implications for understanding the relationship between humanity and capital, in that religious language affords us a certain vocabulary with which to characterize the control which capital exerts over us and over itself. It is like a living thing, and it is something like what Lucretius calls 'an alien mouth' in De rerum natura.

More pertinent to this article, though, is Wright's use of closed feedback loops to describe capital as basically a formal system in a similar way as I did. Capital does not see concrete labor, but only abstract labor as objectified under capitalism (as a symbolic system) through socially necessary labor time. For its input, i.e. monetary capital, it seeks to maximize output as surplus value (Wright says profit, which is probably not incorrect here, though it is worth explicating the difference between the two as always). Understanding capital as a feedback loop, and not just money that begets money, helps us understand Marx's own seminal analysis of capital. It also allows us to view capital in the context of feedback loops which we have consciously designed, giving us a common language with which to talk about it. That is to say, abstraction here is as ever at the root of it.

[1] The point of use-value is that society would not spend effort producing goods if it did not find them useful—not in the sense of being handy, but in the sense that it is something worth producing for someone to consume. We could phrase it as social demand.

[2] This reading of Marx is complicated if you consider value not to be a thing in a cloud and money the thing that exists on Earth, but rather money to be the realization of things being socially valued in real time. As I understand it, this is Heinrich's reading of Marx and it solves a lot of classical problems such as the 'transformation problem' (from value to money), and it also problematizes notions such as superprofits where things are sold for more than they are socially valued.

[3] Of course, this is cumulative for commodities that consume other commodities' use value in their production. A burger, for example, contains the existing social-values of a beef patty, a pickle, and a bun. What is added to the burger in terms of social-value is the time society expects to spend on turning the ingredients into a burger.

[4] https://ianwrightsite.wordpress.com/2020/09/03/marx-on-capital-as-a-real-god-2/

Comments

Post a Comment